- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Evidence summary

- Chapter 3: The Integrated Approach

- Chapter 4: Self care, rights and wellbeing

- Chapter 5: CPD and Career development

- Chapter 6: Practice Supervision and Practice Leadership

- Chapter 7: Mentoring and Coaching

- Chapter 8: Tools for Teams (forthcoming)

- Chapter 9: Tools for Organisational Managers and Leaders (forthcoming)

- References and Bibliography (forthcoming)

Full toolkit in downloadable PDF will be available shortly.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Background

On these webpages you will find the summary of the third edition of our Social Workers Wellbeing Toolkit. The full toolkit will be available to download from the end of July 2025. First published in 2020, this toolkit has been updated and rewritten to inspire and guide change in working conditions and wellbeing of social workers across the UK.

The toolkit is based on evidence from recent research into social workers’ experiences and calls for change. Social workers in the UK consistently report significantly poorer workplace wellbeing than most occupations using comparative measures (Ravalier 2023).

The social work sector in the UK has woken up to the necessity for change since the earlier editions of the toolkit. This has come from social workers being heard and represented more powerfully in cumulative research, other writing and press coverage. It has also come from wider acceptance of the negative impact on service quality and workforce of poor wellbeing, particularly in the wake of the Covid pandemic.

The pandemic period increased sector awareness of the importance of actions to improve wellbeing in the face of extraordinary personal and professional challenges during that period. Having working conditions that support wellbeing is now more recognised as a tangible entitlement and necessity, not a ‘nice to have’. It is essential for to provide the support our communities deserve.

The 12 Changes

Based on the evidence, we have identified 12 key changes to improve social workers’ working conditions and wellbeing. These are:

- Better access to Continuing Professional Development

- Ongoing career opportunities

- Effective professional supervision and other forms of support and reflection e.g. mentoring, coaching, peer support

- Support for wellbeing and self-care at work

- Protection from harm and support to recover from work related trauma

- Enough social workers and manageable workloads

- Enough time to work directly with people – relationship-based practice

- Good quality management and role clarity

- Fit for purpose technology and digital skills

- Effective leadership

- Positive, inclusive workplaces, free from bullying, harassment and discrimination

- Respect and recognition for social work and fair pay

A holistic, systemic and integrated approach

The 12 Changes are not in priority order in this list and they inevitably interrelate and are interdependent. For instance, good management and role clarity are underpinnings of preventing and tackling bullying, harassment and discrimination; access to Continuing Professional Development is a foundation for career development and also links to learning through reflective supervision, mentoring and coaching.

Each organisation will have its own priorities and no one should feel intimidated or overwhelmed by the number of factors. What this list does is deliberately highlight the importance of promoting better wellbeing through a perspective that is holistic, systemic and integrated:

- Holistic: in that the factors that impact on wellbeing are understood to be interconnected and interdependent, and each needs to be understood in the context of the whole

- Systemic : in that not only are factors interconnected, small or big changes in one part of the human system that is a workplace can have knock on effects across the system, intended and unintended, positive and negative. Even small changes can have a big impact.

- Integrated : in that actions for social work wellbeing need to be embedded in the culture and practices of the whole organisation so they are sustained for the long term

As so many factors have been identified as needing attention, they require the contribution and empowerment of diverse actors. In this toolkit, social workers and the social work profession is at the forefront of this. Too often, tools for organisational and culture improvements are aimed at managers and leaders. This is important because of the power and responsibilities in their hands. This toolkit is aimed also at senior stakeholders but equally at practitioners and anyone who can help improve conditions for social work.

This toolkit is part of the joint UK Working Conditions campaign for change being run by BASW and the Social Workers Union from June 2025.

‘Stronger Social Work, Better Lives is a UK campaign that will be delivered at both UK and four nation level, responding to the specific issues amongst social work communities and employing organisations in each country.

What does the toolkit aim to do?

The full toolkit will provide resources and ideas to use in workplaces to shape improvements, particularly in relation to the 12 Changes that our campaign and the evidence highlight. It will be an operational resource that supports the BASW SWU campaign to surface and tackle issues and empower all involved to act for long term change.

While the toolkit is focused on social workers’ wellbeing, it’s ultimate aim is to ensure social work is effective – able to provide excellent services, supporting and empowering people to improve their lives. Our underpinning ethos is that better working conditions and wellbeing at work are the basis for better practice and better experiences for people using services.

Who is this toolkit for?

This toolkit is aimed as much at social workers as it is aimed at managers, supervisors, educators and leaders. Social work professionals have agency in bringing about change, they are not passive recipients or onlookers to organisational developments.

It is aimed at:

- Social workers in practice – employed, contracted or independent

- Supervisors and practice leaders

- Managers and organisational leaders in all employing or contracting contexts

- Educators and researchers

- Policy makers

- Others directly involved in or developing and supporting social work in diverse work contexts.

Our approach starts from the position that social workers (in direct practice and other roles) are professionals who should be heard, respected, enabled to have positive impact on the conditions in which they work and have a professional responsibility to look after their own wellbeing.

Managers, supervisors, leaders and others have responsibilities to provide the infrastructure and organisational approaches for better working conditions. The tool provides guidance for senior staff and locates this in the need for ‘whole system,’ collective efforts for improvement to promote better practices, outcomes and workforce stability.

Using the toolkit

The toolkit is in distinct chapters that can be read in sequence, out of sequence or used as standalone resources. They provide ideas related to the 12 key changes proposed for better wellbeing and emphasise the need for holistic change that recognises the interrelationship between factors. They include practical guidance, exercises for individual or team/organisational use, and further resources available from BASW and SWU and from others working in this field.

This resource is part of a collective endeavour in our sector to bring about change. Use it to spark innovation and action. The key message throughout is that even small changes - by anyone in the workplace - can bring about meaningful change and do things differently.

BASW Code of Ethics

The BASW Code of Ethics provides guidance and ethical consideration of many of the issues raised in this toolkit and is a valuable companion document.

A summary of evidence: the case for change

The evidence base for the 12 Changes (chapter one) and this toolkit is drawn from recent research about the social work workforce and employment practices in the UK.

The toolkit draws on the extensive primary survey and research collaborations between Professor Jermaine Ravalier and colleagues at Bath Spa and now at Buckinghamshire New University (BNU), BASW and SWU.

Over the past eight years, Prof. Ravalier and colleagues have worked with BASW and SWU to conduct large surveys and extensive evidence reviews of social worker wellbeing and working conditions in the UK which together had over 6000 respondents (Ravalier J. M. 2019; Ravalier J.M. et al 2019a;Ravalier J.M. et al 2019b; Ravalier J.M. et al 2022; Ravalier J.M.et al 2023) Findings from a survey of 3,421 adult, mental health, and children’s social workers in 2021 suggested 50% of respondents were unhappy in their role (Ravalier et al., 2021b). Over 60% of respondents were also planning to leave their current post (but stay within social work) within the next 20 months (Ravalier et al., 2021b).

Since the last version of this toolkit, academic and non-academic research into social workers wellbeing has proliferated and this overwhelmingly substantiates a very concerning picture of poor wellbeing and dissatisfaction with the workplace

It also tends to tell us that social workers love their work and find rewards even when the work is tough. Social workers are motivated by their primary purpose – but are often hindered by working conditions that don’t support it well enough.

Understanding stress

Much of the research identifies high levels of stress. The word ‘stress’ is often used loosely and imprecisely about social workers and in general discourse. But it has a defined and important meaning in relation to workplace wellbeing.

The Health and Safety Executive defines negative stress as: ‘the adverse reaction people have to excessive pressures or other types of demand placed on them’ https://www.hse.gov.uk/stress/overview.htm.

Employees feel negative or overwhelming stress when they cannot cope with pressures and other demands at work, or when they are being poorly managed or led.

Social workers may be particularly at risk of stress as defined above because of poor working conditions that are common in social work such as:

- A mismatch of resources and demand

- Lack of role clarity and boundaries

- Lack of control over workload or decisions

- Insufficient or inappropriate training and development

- ‘Scapegoating’ and blame cultures

- Poor or unsuitable management methods

- Inadequate supervision particularly to cope with complex work

- Inadequate support following serious incidents (such as an assault or a death)

Chronic stress at work and burnout arises when workers experience these types of working practices and cultures persistently.

The reasons for stress and poor morale in social work

The reasons for widespread stress and poor morale in social work has been increasingly researched. The pressures of too few resources and high workloads negatively impact work/life balance (Kinman 2021) and multiple stressors such as high demand, high bureaucracy and poor supervision can cause burnout (McFadden et al., 2015). Consequently, social care professionals are at greater risk of work-related ill-health including stress, anxiety, and depression than many other occupational groups (Health and Safety Executive, 2023).

Unsurprisingly, experiencing burnout has been associated with intentions to leave a job or the profession (McFadden, 2015b; Zielinski et al., 2021).

These are issues for social work across the UK with particular hot spots. For instance, an overview of social worker working conditions and wellbeing research for Scottish social workers in 2021-2022 by the Scottish Association of Social Workers (SASW part of BASW 2022) reported that:

‘Overall stress scores for social workers were much higher (in Scotland) than the UK average. Over a third have suffered an emotional response, either crying or feeling unwell, at their work at least once a week. In Scotland 50% described their current caseload as ‘not at all’ manageable’ (SASW 2022, p1)

Retention

The post-Covid phenomenon of worsened retention of social workers across the UK has been particularly influential in bringing evidence of poor working conditions and wellbeing to the attention of policy makers, employers and development bodies across the UK.

For instance, high numbers of leavers from the children’s workforce in England led to increased reliance on agency staff giving rise to workforce instability and high costs (Department of Education, 2023). This led to statutory guidance on employment of agency workers being issued for children’s social work in 2024.

Similar concerns were raised in Northern Ireland and in 2023, all of the main statutory employers of social workers (the Health Trusts), stopped using agency staff in pursuit of a stable workforce. Northern Ireland is also developing a pioneering model of ‘safe staffing’ that seeks to bring parity between social workers and other health staff employed in their integrated NHS Trusts (see https://basw.co.uk/safe-staffing-and-social-work-working-conditions).

Loss of experienced staff in recent years has been a particular concern for ongoing workplace wellbeing as these staff are essential for mentoring, supervision and peer support within social work teams. The Review of Children’s Social Care in England identified significant concerns about inexperienced practitioners holding complex and high-risk safeguarding caseloads (MacAlister, 2022).

Evidence has started to emerge about the importance of maximising ‘pull factors’ to incentivise social workers to stay (Cook et al., 2022; Biggart et al., 2017) through ‘addressing organisational culture, strengthening peer and team support, and providing CPD opportunities tailored to the specific career stages of social workers’ (Cook, L . 2024, p7)

Tackling racism and all forms of discrimination

Research indicates that social work reflects the intersectional inequalities of wider society across the UK; women achieve disproportionately fewer senior roles than men; white social workers are promoted disproportionately more than black and global majority colleagues; black social workers – and particularly black men - are disproportionately referred for fitness to practice reasons to the regulator in England (Social Work England 2024); emerging research into neurodiversity amongst social workers indicates the profession mirrors the lack of awareness and provision of reasonable adjustments experienced by social workers with other disabilities and long term conditions. (Koutsounia, A. 2022);

The What Works Centre in England found one in ten social work respondents in a survey of 2000 social workers had considered leaving their organisation because of racism and nearly one in five respondents (19%) reported that workplace racism had increased their anxiety, and 13% reported worsened mental health.(WWC 2022).

The DfE in England found that representation of black social workers halved from 20.5% of the workforce in frontline practice to 13.1% of senior social workers and 10.5% of managers – starkly illustrating inequality for black social workers in career pathways.

Similar findings about the incidence of racism and its impact on wellbeing, mental health and intentions to leave the profession have come from recent surveys in Scotland (SASW 2021; IRISS 2025) and Wales (BASW Cymru 2022; Social Care Wales 2025). Across all nations we see the development of workforce race equality action plans by governments, regulators and other bodies to make anti-racism a reality across the sector.

BASW’s survey of social workers in 2023 found 41.15% reported bullying, harassment and/or discrimination against themselves in the past 12 months, or were aware of someone else in the workplace who had been affected (BASW 2024).

Taking action on racism and all forms of discrimination is an ongoing wellbeing and social justice priority and challenge in social work workplaces. Action on wellbeing is a vital response to the evidence base - and human stories of harm and hurt that lie behind the statistics.

Comparisons with other occupations: the HSE Management Standards

Research led by Jermaine Ravalier has had the additional benefit of using methods that enabled benchmarking social worker wellbeing with that of other disciplines, and of undertaking repeat surveys using the same measures.

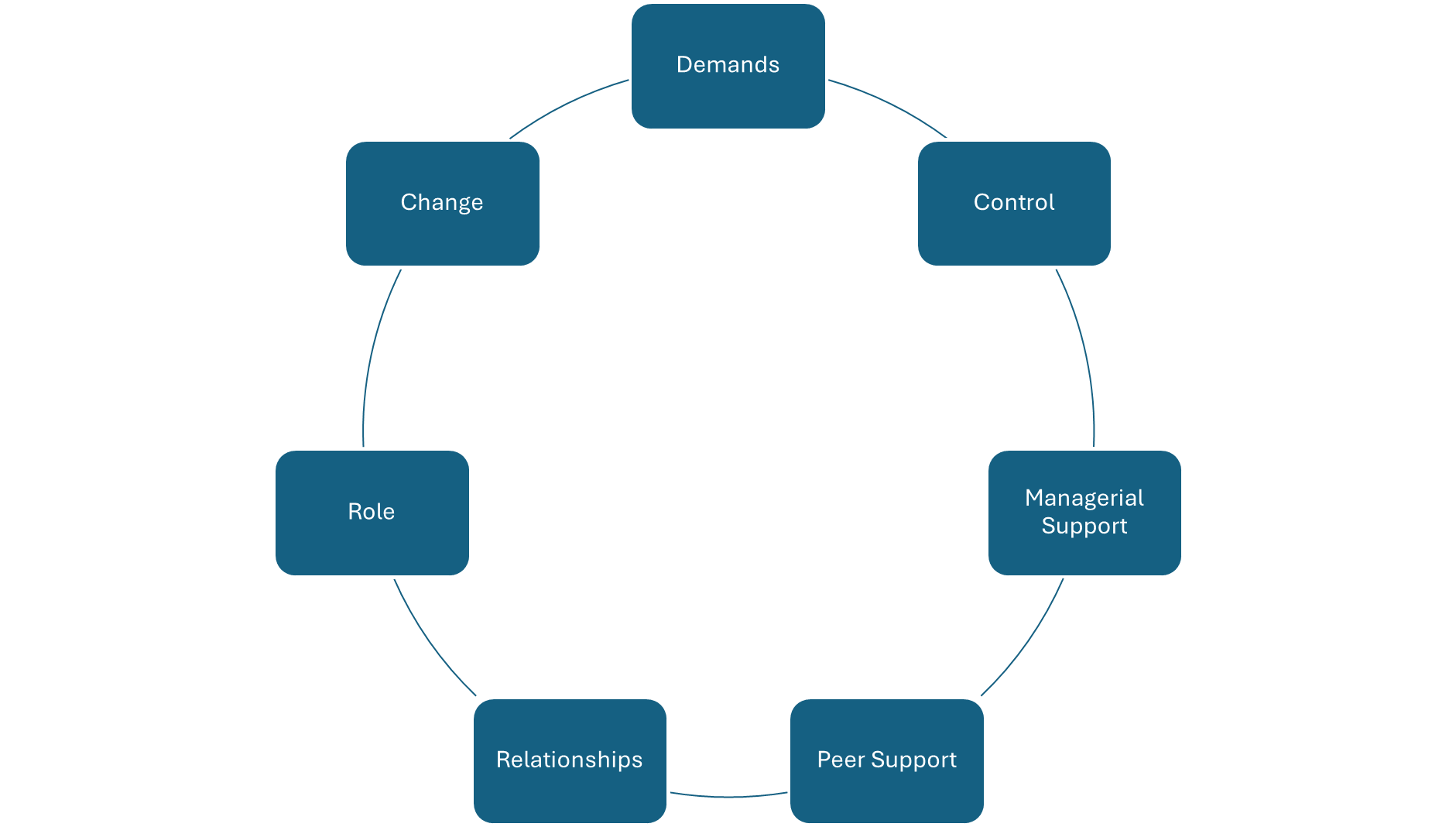

Amongst other measures, the research addressed factors identified by the Health and Safety Executive Management Standards (see www.hse.gov.uk/stress/). Released in 2004 the ‘management standards’ are based on 7 key factors known to affect working conditions and workplace stress.

The HSE approach has been used widely, including in public professions, over many years, although less frequently within social work until this recent work (Grant and Kinman 2014; Ravalier, 2019; Ravalier et al 2023; Ravalier 2023). This has meant useful comparisons are possible across occupations.

The Health and Safety Executive Management Standards

When the seven Standards are well addressed and function at optimal levels, employees can thrive. Alternatively, poor practices or imbalances in one or more of these areas can lead to poor conditions of work and have a negative impact on employee health and wellbeing, turnover and sickness absence, amongst many other staff outcomes (Mackay et al., 2004; Ravalier, 2019).

For instance, if demand exceeds reasonable capacity, workloads will become unmanageable and pressured leading to unmanageable stress. If workers have too little control and autonomy in deciding how they do their work and use their time – particularly professions such as social workers dealing daily with novel challenges and human emotions – work may be unsatisfying, less productive, more negatively stressful and less well ‘owned’ by staff.

Research by Ravalier et al (2023) found very poor comparison of UK social workers with other benchmark for occupations and organisations:

In the latest iteration of this survey (2022), the measure of psychosocial working conditions….was still consistently poor. Indeed, each of the demands, control and change sub-factors scored at the fifth percentile or lower—worse than 95 per cent benchmark respondents in other organisations. Managerial Support and understanding of the Role played scored in the 10th percentile, and Peer Support and Relationships slightly better in the 25th percentile, although still worse than 75 per cent of benchmark scores.

Ravalier J.M et al (2023)

These findings are stark, worrying and deserve significant attention by employers, policy makers, politicians and by the profession itself. The research summarised in this chapter is the basis for this toolkit and the BASW SWU campaign for change.

An Integrated Approach

The research explored in chapter two points to the importance of seeing the workplace as a human system of interrelated factors. In human systems (like families and communities) we know that change in just one part can sometimes have a big impact on other parts (positive or negative). Improvement often require changes and adaptations across the system and taking a holistic, systemic and integrated perspective can be important to understand and take into account interdependencies.

- Holistic: in that the factors that impact on wellbeing are understood to be interconnected and interdependent, and each needs to be understood in the context of the whole

- Systemic : in that not only are factors interconnected, small or big changes in one part of the human system that is a workplace can have knock on effects across the system, intended and unintended, positive and negative. Even small changes can have a big impact.

- Integrated : in that actions for social work wellbeing need to be embedded in the culture and practices of the whole organisation so they are sustained for the long term

This is the approach to workplace wellbeing explored throughout the toolkit and includes encouragement to consider the role of all stakeholders in making change

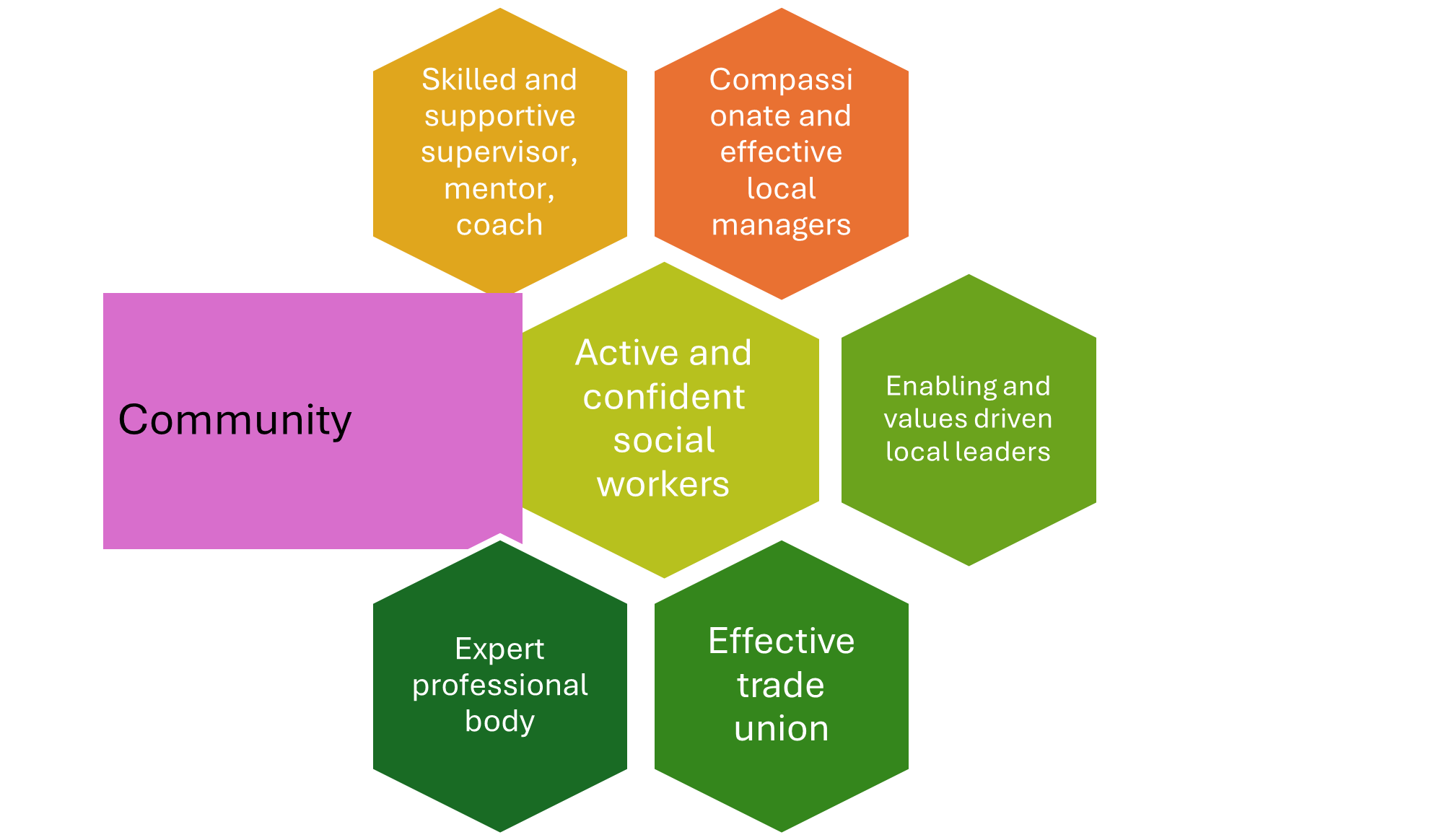

The Integrated Approach to Change (2025)

The Integrated Approach (2025) represents the interaction and interdependence between social workers, supervisors and practice leaders, teams, managers, organisational leaders, professional organisations and trade unions who all have part of the responsibility for making changes and working together better to enhance social workers’ wellbeing.

Responsibility and power to effect change is not just hierarchical; change by managers and leader may be necessary but is not sufficient without the engagement and contribution of social workers themselves.

Social workers have professional capability and responsibility to make their professional needs known, to influence ‘up’ the system, to challenge failings (e.g. in care or resource availability) and show professional leadership rooted in their practice and ethics.

To do this, social workers need access to information, and this often needs to come from the wider profession not just from within their organisation. They often need the support of their professional body, other collective professional groups, and their trade union to know their rights and benefit from being active within their professional community.

Accounting for the structural context of social work

The Integrated Approach also takes account of the situation for the communities social workers serve. Inequality has increased in the last fifteen years across the UK and public sector resources have reduced in real terms. This has driven demand for social work and made addressing needs and social injustices more difficult.

Addressing wellbeing in the perspective of this toolkit is a radical and necessary act - to sustain social work’s hope, resilience and collective solidarity in our mission for a more just society. Workng in structural contexts of deep inequality, inadequate funding across health and social services and real terms pay cuts make ‘radical wellbeing’ even more essential.

A highly unequal society

Unlike many models of workplace wellbeing, our approach includes recognition of the impact on social workers of the wider social, economic and community contexts for practice. Social work is now largely focused on supporting people who are most marginalised in society for reasons such as poverty, discrimination, social and legal exclusion, neglect, crime, and trauma.

As well as helping people use their strengths and potentials, social workers often act as holders of hope and protectors of human rights through the most difficult times, while acting as gatekeepers, advocates and brokers of (sometimes insufficient) public services.

Fifteen years of public sector, welfare and economic austerity have increased poverty and inequality in society as a whole https://equalitytrust.org.uk/scale-economic-inequality-uk. Demand for social work services has risen while the means and resources available to public services to meet them have declined. This has increased the gatekeeping role of social workers (particularly in statutory services), reduced early, preventive work and reduced the availability of community and voluntary sector resources in many localities. These factors can require social workers to implement narrower eligibility criteria.

Tackling social justice and inequality issues, and helping people find their own paths to better lives, is part of the huge reward of social work. But it can also make social workers distinctively at risk of a demand/capacity imbalance, leading to stress and burn out. The ask of employers, managers and leaders is that they understand and support social workers in the reality of their job.

Resourcing the workforce

Resourcing social work practitioner terms, conditions and pay is a challenge across the UK. The state of public finances across the UK is poor and unlikely to improve soon. It is well known that real terms investment in statutory social services has declined through the years of austerity (at least 10% in real terms in English Councils, for instance with wide variation, and similar in Scotland and Wales) while demands and populations have risen, and other community sources of support and preventive help have declined.

This toolkit – and the associated BASW and SWU campaign for ‘Stronger Social Work, Better Lives’ – takes account of the need to press for more investment in social work roles and careers while encouraging improvements through the powers and levers available now within our sector. This includes harnessing the evidence better, taking collective actions as a profession, improving organisational cultures and sector leadership, and recognising the potential of changes in interlocking systemic factors that can shift to bring about change.

Looking after yourself at work

Social workers need to look after their own wellbeing at work. But as committed, helping professionals - sometimes delivering support in urgent or ‘last resort’ situations - social workers can neglect or downplay their own wellbeing needs.

The full version of the toolkit will includes more selfcare and wellbeing tools but below are the key messages.

Our research has shown that social workers frequently work additional unpaid hours shows how they go ‘the extra mile’ for the people they work with – and also indicates that there aren’t enough social workers in many teams to cover all the work. This leads to cycles of overwork and lack of time for self-care and reflection, undermining health and wellbeing.

Employers are responsible for creating good conditions for wellbeing. Social workers are responsible for identifying and finding ways to meet their particular health and wellbeing needs – ideally in partnership with their employer and managers.

Understanding our own wellbeing

Wellbeing at work can be thought of broadly in terms of our psychological, social, and physical health. Many people would also include spiritual wellbeing. Poor wellbeing undermines practitioners’ lives, their ability to do their job, and may lead to acute or lasting physical and mental health problems.

Being in a state of good health and wellbeing certainly means being free from - or able to effectively manage – illness, pain, loneliness and/or mental distress. But pursuing a wellbeing culture at work means more than this; it means organisations and all working in them actively pursuing a positive state of thriving, and taking regular, early action to care for and respect oneself and others. This requires consistent, active attention.

When stressors are high over long periods it is important to be consciously alert to your state of wellbeing and health and actively balance negative experiences with restorative activities. This includes constructive reflection and supervision, and time to turn experience into growthful learning.

While this toolkit provides guidance for employers, managers and leaders on what they can do to uphold the rights of their staff and improve wellbeing, it also puts social workers themselves in the driving seat of improving their own wellbeing - and helping to make their teams and organisations better places to work.

Understanding employers responsibilities for workplace health and wellbeing

While improving wellbeing takes effort from (and is a professional responsibility of) social workers themselves, the roots of poor wellbeing and health often lie in employers’ failures to protect workers’ rights and tackle negative working cultures and norms such as:

- regular working over contracted hours;

- not having time for breaks;

- not having support and time to recover and make sense of difficult incidents;

- instances of practitioner ‘moral injury’ : where practitioners know the right and professional thing to do, but lack the resources, mandate or support to achieve it

- unclear job roles and lack of permission to manage one’s own workload

Knowing your rights at work

Knowledge is power and social workers need to have knowledge and useful tools to identify their formal rights entitlements (statutory and contractual), to push for consistent dignity and respect at work, and to be able to ask their employers for improvements. Key sources of knowledge and power include:

- Knowing your organisation’s policies and procedures supportive of wellbeing

- Know how your organisation monitors wellbeing and how you can feedback

- Join and use the resources of a trade union

- Discuss concerns or ideas for improvement with colleagues and managers

- Ask for a CPD session on your rights at work

It is important not to delay seeking advice if you think something is wrong (e.g. in how you are being treated or in what you are being expected to do). It is also important to seek early help if you are struggling.

Actions: exercising your rights at work

Tips on exercising your rights at work

- Seek help as early as possible if something doesn’t feel right: go to whoever it feels right and safe to approach which could be a peer, a union representative, a manager or supervisor, someone in human resources, or someone from an independent Employee Assistance Scheme.

- Make sure your employer provides you with all relevant policies on health, safety and wellbeing such as all the different types of leave that you can apply for; flexible working options; sources of employer support e.g. through Employee Assistance Schemes, employer-funded counselling, or a referral to Occupational Health;

- If it feels necessary and safe to do so, speak to your supervisor and/or manager about how the organisation can support you better

- If matters persist, speak as early as possible to the BASW SWU advice and representation services or your separate trade union which can provide you with information about your rights and support you talk to your employer

- If it feels right, talk to trusted colleagues about how they can help you

- Make a personal plan to fill any gaps you have in your knowledge of your rights and sources of support and information

For more information on your rights at work, see information from BASW and SWU on the BASW website https://basw.co.uk/support/advice-representation

Tackling Bullying, Harassment and Discrimination

Recent research on social worker wellbeing has found that unhealthy management and peer cultures persist in the workplace. This includes considerable evidence of bullying, harassment and discrimination including racism in workplaces and in the course of practice. This leads to high intentions to leave jobs or the profession amongst some global majority colleagues.

In the BASW social work survey (BASW 2024) we found two-fifths of respondents (41.15%) reported that they had experienced bullying, harassment and/or discrimination or were aware of someone who had, an increase on previous years.

No social worker should suffer such treatment at work. A wealth of resources are available from trade unions including SWU, from BASW and from other organisations such as ACAS (https://www.acas.org.uk/about-us) the Arbitration and Conciliation Service for England, Scotland and Wales and for Northern Ireland, the Labour Relations Agency https://www.lra.org.uk/About

You are not alone

Seeking help and advice in a timely way can be difficult. For instance, it can be hard to recognise treatment by colleagues or managers as unacceptable until it has escalated. You may feel shame or your self-esteem and personal agency may have been undermined making it hard to reach out for assistance. The treatment may be disguised and hard to pin down or describe. The culture or practices of the organisation may make it difficult to raise issues safely.

In short, social workers may not know where to turn until matters have got worse.

It is important to try and speak of any unease or suspicion you have that bullying, harassment or discrimination is happening as early as possible.

- Talk with a trusted colleague in your organisation about any concerns you have as early as possible

- Consult your organisational policies and see where you can go for help

- Talk with your trade union or professional body

- Be a trusted confidante for your colleagues, look out for and call out poor treatment affecting those around you

- Remember that bullying, harassment and discrimination are the fault of the perpetrator, not the victim

- Remember that certain behaviours may be criminal or employment law offences and you have the right to protection in law

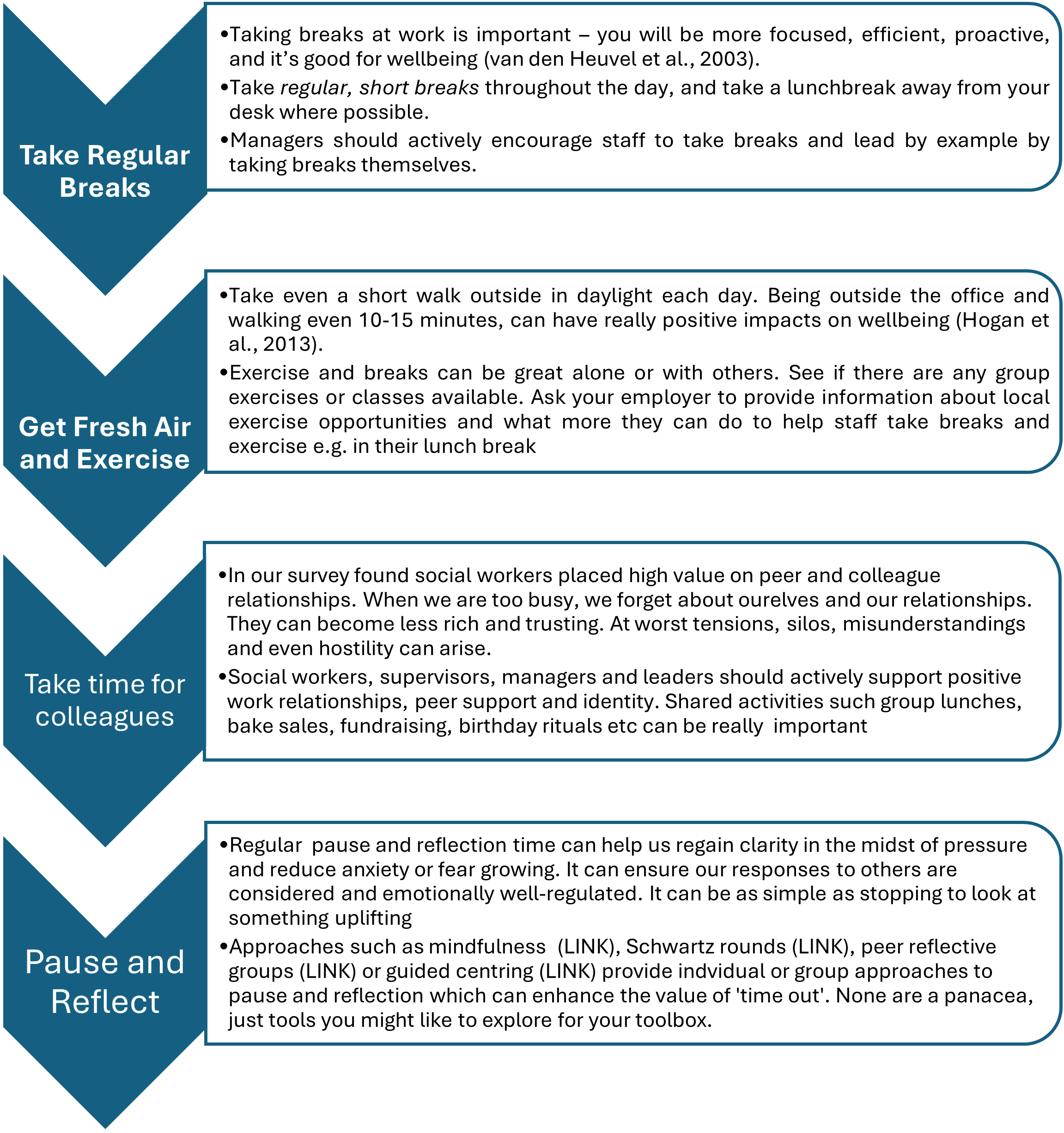

Self-care

Self-care at work is about finding ways - large or small - to prioritise ourselves, assert our right to dignity at work, and to take back control of time and space to focus, reflect and restore ourselves.

It includes know your rights, as described above, and actively creating support and time to protect and restore your health and wellbeing.

Remarkably small self-care actions can make a big difference. Below are four simple self-care actions at work that may help anyone take more control of their wellbeing and set in train healthier patterns.

Self-care outside of work

To do the valuable job of social work well for the long term – and to be emotionally and intellectually available for people requiring your support - means looking after yourself well inside and outside of work. You are encouraged here to explore ways to greater wellbeing that might work for you and to think about whether there is anything stopping you caring for yourself that bit better.

Our health at work often depends on our work-life balance – or the work/life ‘fit’ that works for you. Making changes towards healthier self-care practices in our personal lives can help work health, grow our confidence, stamina, and physiological and psychological capacity to deal with stressors at work.

Building healthier eating and drinking habits into our daily routine, reducing or stopping smoking, increasing exercise and relaxation time, finding ways to sleep better, ‘switching off’ taking a ‘digital detox’ and making time for friends and family – we all know these are important. We all have days when we reach for a glass of wine, an ‘unhealthy’ takeaway, or a cigarette. This can be fine and fun and part of human coping – as long as it doesn’t happen too often (Polivy & Herman, 2005).

Being honest with ourselves

Social work can sometimes feel like an ‘always on duty’ vocation. Social workers sometimes feel guilty about the privilege of being able to make choices to live well and better when working with people in great disadvantage.

Take time to reflect on whether your beliefs about yourself, your role in life and as a social worker get in the way of improving your self-care and balance between work and personal life. Here are a few questions which might help you start your reflection.

|

Moral and ethical stressors

Social workers can find themselves negatively affected by being restricted from acting and/or unable to help people who are in severe need - or being required to work within policies that contradict professional ethics, standards, or expectations. This may be because of raised eligibility criteria, reduced funding, unfeasible workloads, practitioner and administrative staff cuts, lack of time for relationship-based practice, bureaucratisation, or a combination of all these and more.

Social workers are often particularly tasked with sustaining ethical working practices in unethical systems and real world context.

- ethical overload - being faced with too many choices

- ethical confusion - in not knowing the right action to take

- ethical stress - anxiety about making the right decision

- moral distress - feeling negative emotions about being unable to do the right thing

- moral injury - damage to the moral self by actions that violate core moral beliefs, resulting in guilt, shame and hopelessness.

(After Sarah Banks, PSW 2022)

‘The concept of moral distress is useful in describing the experiences of social workers when they are unable to practise their profession according to their moral code and the emotional burden related to this inability.’

(Mänttäri-van der Kuip, 2020, p.86)

Such situations are most likely to cause deep problems when they are repeated experiences and/or when social workers do not have the opportunity – the time and skilled support - to reflect, recover and learn from their experience. It is crucial that managers and leaders understand social workers’ experiences and build wellbeing support that takes account of particular stressors.

Guidance on working with people in poverty

BASW has produced guidance for social workers on anti-poverty practice, (see BASW anti-poverty practice guide https://basw.co.uk/policy-and-practice/resources/anti-poverty-practice-guide-social-work which helps to empower practitioners to find ways to act and be helpful in contexts where people are facing (often) complex, structural, personal and material disadvantages. This includes understanding social determinants and socio-economic policy context affecting communities and society and understanding how to integrate this into day to day, relationship-based practice while sustaining your wellbeing.

When personal challenges affect wellbeing at work

As social workers, we face all the same challenges and opportunities in our personal and family lives as anyone else. Common stressors in our personal lives might include:

- Caring responsibilities

- A long-term health condition or disability

- Personal trauma or tragedy

- Financial difficulties

- Relationship breakdown or family discord

- Domestic abuse

- Bereavement

- Mental health/emotional difficulties

When things are hard outside of work it is important to understand how to ask for support as early as possible. Developing your personal approach to seeking support, and building and maintaining support networks, are important professional and personal skills.

It is important to understand your rights in law and in local/organisational policy for help with some personal challenges. Local employer policies are an important starting point, as are national and governmental organisations. For instance, Carers UK provides excellent up to date UK level information your rights at work and sources of support. https://www.carersuk.org/help-and-advice/work-and-career/

BASW, the Social Workers Union and other Trades uUnions are key sources of support when personal or work based challenges affect you and your work.

It can be helpful to pause, be honest and take stock of what is happening in our personal or home life that might be a tangible stressor affecting you private and work life. Below is a suggested self-completion checklist to aid reflection. This is not a formal or validated self-assessment tool. It is adapted from evidence-based assessment tool (Holmes and Rahe 1967) and tools used in relevant UK organisations (e.g. the Northern Ireland Health and Safety Executive (https://www.hseni.gov.uk/) . It is a prompt list for reflection.

Personal agency and choice: is this the right place for me now?

Allow yourself from time to time to consider ‘Is this place right for me? Does it deserve me? Could I flourish and offer more elsewhere?’. The answer might be

- This place is right for me

- This place could be right for me if I make some changes

- This place could be right for me if my employer/manager/supervisor make some changes

- This place isn’t right for me and I don’t think change is likely

The job market, economy, personal circumstances, and the nature of social work services can shape and limit our choices. But as qualified people with skills needed over the whole of the UK, social workers do have more choices than many. It is important to remember this and use our choices ethically.

The public service ethic of social work – including deep commitment to the people we support and to tackling injustice and social issues – risks working against social workers using their personal agency and asking themselves.

Resilience

Social work throws up new challenges and makes new demands on practitioners every day. The emotional, intellectual, and practical labour – and the nature of the decisions and responsibilities taken – mean social workers need a particular kind of interpersonal and professional resilience to do and sustain the amazing work they take on.

There has been a lot written and disseminated across the UK social work sector on practitioner ‘resilience’ recently. Louise Grant and Gail Kinman (Kinman and Grant 2014) have summarised the main dimensions of social worker professional resilience as emotional intelligence (Goleman 1996), reflective thinking skills, accurate empathy, and social skills.

Resilience is a controversial term when it is used to describe a wholly or largely internal or ‘intrinsic’ set of qualities within individual workers. In our approach, resilience is understood to be something that arises through the interaction of an individual’s personal coping strategies, self-development and self-care and the context in which people work - the demands, expectations, ways they are treated and supported in the workplace.

A key to sustaining adaptability and resilience in the workplace can be ensuring ‘psychological safety’. This these is picked up in the section on supervision and the companion sections on mentoring and coaching. The nature of social work in psychologically challenging and requires safe, skilled, reflective support to enable recovery from trauma (direct and vicarious), to provide safe spaces to talk about discriminatory challenges such as experience of racism, and to support the synthesis of experience, evidence and emotional connections into learning and enduring confidence.

Social workers are not powerless over their wellbeing in the workplace. There are many things we can all do to improve wellbeing. Knowing about these – and giving yourself permission as a social worker to really care about yourself – is your right as a worker and a professional.

This can include social workers:

- developing more skills in influencing their organisations,

- widening their sphere of control,

- gaining confidence to advocate for themselves, for people using services and for organisational or practice changes.

- Using the support of BASW and their trade union

Continuing Professional Development (CPD) and career development

Continuing professional development (CPD) is a cornerstone of professionalism. It is essential for social workers in direct practice and in any other social work-related role.

Amongst other things, it is key to ensuring:

- high quality and up to date practice

- valued outcomes for people using services – particularly where learning is co-produced

- higher social worker satisfaction, wellbeing and professional confidence

- promoting recognition of social workers’ professionalism

Employers and leaders are responsible for providing resources and time for CPD – not least to ensure staff are updated on their responsibilities under organisational policies.

Social workers are professionally responsible for seeking and carrying out relevant CPD to maintain their registration, ensure they can uphold regulatory standards of capability and ensure they are up to date in their wider skills, knowledge and ethics.

Nation specific CPD frameworks for social work Completion of CPD is required by all the social work regulators in the UK, although their approaches are different. Registered social workers in each nation need to know how to meet regulatory CPD requirements. But it is equally important that employers, managers and leaders in all organisations also understand the access to CPD that social workers need. Employers also need to understand the specific responsibilities of upon employers as laid out in employers’ standards or codes in each nation. The main CPD and employers’ responsibility frameworks for each nation can be found via these links to the regulators: England: Regulatory requirements https://www.socialworkengland.org.uk/cpd/ Employers standards: https://www.local.gov.uk/our-support/workforce-and-hr-support/social-workers/standards-employers-social-workers-england-2020 Northern Ireland: Regulatory requirements: https://learningzone.niscc.info/post-registration-training-and-learning/ Employer Standards: https://www.rqia.org.uk/guidance/guidance-for-service-providers/standards-for-employers-of-social-workers-social/ Scotland: Regulatory requirements and Codes for Employershttps://www.sssc.uk.com/supporting-your-learning/workforce-development/ Wales: Regulatory requirements: https://socialcare.wales/registration/continuing-professional-development-cpd Employers Codes: https://socialcare.wales/cms-assets/documents/Employers-code.pdf |

The value of CPD to wellbeing

Access to relevant and good quality CPD activities and reflection time refreshes and inspires practitioners. It can reconnect social workers with the values, ethics and what brought them into the profession in the first place. It can also be a vital tool in dealing with difficult or traumatic work experiences and preventing and addressing signs of burnout.

CPD promotes wellbeing and satisfaction in the workplace by supporting social workers to:

- Develop and have confidence in their skills and knowledge to do their job well

- Stay open and curious to new ideas and new evidence

- Connect with peers through shared learning experiences – online and in-person

- Build and reframe their relationships with people using services e.g. through co-produced activities and learning discussions centred on lived experience

- Increase their intellectual and professional resilience to deal with challenges, dilemmas, trauma and new situations

- Progress in their career aspirations and professional motivations – within or beyond their current workplace

- Contribute to the development of the profession and knowledge creation beyond the ‘day to day’

- Have a sense of pride and achievement in their work

- Feel respected and nurtured by their organisation

What other wellbeing benefits for social workers of more access to CPD would you add to this list?

Making time for learning

Despite the fundamental necessity for CPD, research shows that too often employers and managers provide insufficient opportunities and time for learning. In particular, it is rare for employers to provide protected time for CPD activities and consolidation of learning other than that afforded to newly qualified practitioners

Protected time is quite common in other professions, for instance in healthcare. In social work, culture, operational norms and ‘taken for granted’ expectations can also allow time for learning to be squeezed out and deprioritised. These norms may become accepted or internalised by social workers themselves as well as by employers, managers and leaders.

To turn this around and make time for learning and reflection, social workers, employers and leaders should work together in the prioritisation, commissioning and provision of learning activities, and in harnessing the potential of the curiosity and ambitions professional social workers can bring into workplace. Organisational and practice leaders need to demonstrate their commitment to changing culture and show strong leadership and vision.

Asking for time for CPD

If there is little time for CPD in your workplace, consider asking for a trial initiative

If you work/mange within an organisation where there is no/insufficient protected time for CPD consider the following

|

Diversifying forms of learning

CPD can take many other forms and social workers are involved in increasingly diverse activities within and beyond the workplace, particularly as digital and online formats proliferate. CPD can take the form of:

- An accredited or unaccredited course of learning/training: in person or online

- Reading and reflecting on texts, films or podcasts

- Speaking and reflecting on views and feedback from people using services

- Discussions within supervision, coaching or mentoring

- Peer discussions or supervision within your organisation or other contexts

- Being active in a wider community of social workers e.g. through communities of practice, Special Interest Groups and being part of the professional body, BASW.

- Undertaking reviews, audits or research activities

- Creating and sharing knowledge through writing, making podcasts, films etc.

- Learning through a social work Trade Union

What other activities help you learn?

Employers and leaders have the opportunity to understand and tap into social worker-led diversification of new forms of learning and the evident motivation in the profession, potentially aligning and integrating these into in-house courses and CPD programmes on organisational priorities.

The proliferation of learning approaches should be celebrated and embraced in the workplace. One of the advantages of more informal activities is that people can fit them into their day – in working time, on their commute or lunchtime. While this does not compensate for the lack of protected time, listening to a podcast or catching up with an online forum can be a pragmatic and often welcome way in which social workers can take some learning time.

Managing Artificial Intelligence and Digital Learning

The burgeoning availability of online material about social work means ideas and information can spread quickly and widely. Sources of information are diversifying and many are not subject to ethical, evidential or good practice scrutiny. They may amount to misinformation or poorly framed, inaccurate ideas. This is already a major concern for social work educators and includes tackling the covert use of increasingly convincing AI generated text within assignments and easy access to unresearched or poorly conceptualised content from the internet.

The impact of rapidly spreading artificial intelligence- generated material needs to be understood by social workers, employers and leaders in the workplace as well as in educational contexts.

Through peer dialogue and managers/leaders engaging with social workers about the value and downsides of ‘unregulated’ sources, social workers and their employing organisations can promote the value of curiosity and diversification of learning while also bringing in necessary critical evaluation of diverse influences and sources.

BASW has produced initial practice guidance for social workers on generative AI https://basw.co.uk/policy-and-practice/resources/generative-ai-social-work-practice-guidance

Enabling social worker engagement in research and academic work

Employers can provide and encourage CPD that stretches and extends professionalism and enables social workers to grow, develop and explore their future as well as their current practice. This may include enabling social workers to be involved in research and other academic activities within local university and research partnerships, or through applying for a funded opportunity from one of the national research bodies.

Access to post-qualifying formal research, publication and dissemination activities has improved in recent years in England with the development of National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) funding for social care research and the establishment of the School for Social Care Research (SSCR). This includes the development of programmes to prepare social workers (and others in social care) for research. More information is available on the NIHR website here https://www.nihr.ac.uk/career-development/support-by-profession/social-care-practitioners and for SSCR here https://sscr.nihr.ac.uk/about/

Key resource: Research Advisory Group for the Chief Social Worker for Adults (2023) A Charter for Social Work Research in Adult Social Care. Birmingham: BASW.. The Charter was commissioned in England but with direct relevance to the whole UK . Access here https://basw.co.uk/policy-and-practice/resources/charter-social-work-research-adult-social-care

CPD for all career stages

CPD and different types of organisational learning opportunities and approaches need to respond to social workers’ requirements and ambitions at all stages of their career. Equally, social workers need to take ongoing responsibility for their CPD, to refresh and challenge themselves, to take on new evidence and ideas and deepen their knowledge and skills. This supports experienced social workers to take on new practices, roles and responsibilities with confidence and skill; and to sustain and to sustain their social work identity, values and ethics in alignment with contemporary perspectives.

Social work managers and leaders also need to engage in their own ongoing professional social work learning and development. Learning and curiosity are lifelong professional commitments and necessities for enabling effective practice in others as well as oneself. Being experienced or advanced in practice or in a non-practice senior role does not reduce the need for reflective and critical learning.

A continuing focus on their own professional development supports managers and leaders in promoting social work values and ethics as a ‘golden thread’ through their decision making, planning, strategy and operations within organisational and multidisciplinary systems. Too often, social workers in direct practice experience a disconnect between the ethics, values, practice priorities and critical analysis of their work and the approaches driving their employing organisations. CPD – ongoing learning and reflection - for social workers in senior roles helps to connect direct practice concerns with organisational concerns and decisions.

The Professional Capabilities Framework (PCF) in England is a very important tool for the promotion of whole career learning and coherence of values and across generic skills as one unified profession https://basw.co.uk/training-cpd/professional-capabilities-framework-pcf

A Learning Culture

Committing to career long learning for social workers can be part of building an organisational ‘Learning Culture’. There are many definitions of this and there no unifying concept or theory but it includes:

- Supporting individual learning and transformation which influences strategy and processes

- Encouraging teams to learn and reflect on their work and proactively influence strategy and processes

- A willingness to learn and improve across the organisation/system and amongst key decision makers.

After: CIPD (2020) Creating Learning Cultures: Assessing the Evidence. Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development

Practice supervision

Effective supervision is essential for social work. Amongst many factors that create a fruitful working relationship, supervision needs to be:

- Accessible, Sufficient, Timely

- Critically reflective

- Provided by a skilled and knowledgeable supervisor

- Consistent, Reliable, Safe (psychologically and otherwise)

- Provided in a suitable, private and comfortable space

- A joint endeavor between supervisor and supervisee

- Focused on enabling valued outcomes and experiences for people using services

- Able to ethically support compliance with required professional standards and policy

- Underpinned by positive social work values and ethics of promoting equality, rights and justice

High quality supervision is important for social workers’ wellbeing at work. At its best, it provides a vitally important space to work through and beyond the emotional, intellectual, and practical challenges of work. Supervisory discussions help to ‘unstick’ thorny issues, reduce the risk of vicarious or direct trauma and help social workers stay connected with the reward of good work done.

The BASW Supervision Guide provides principles for supervision based on the UK Code of Ethics and good practice evidence which all social workers in the UK can use to assert their right to effective supervision. It defines supervision as:

‘a regular, planned, accountable process, which must provide a supportive environment for reflecting on practice and making well informed decisions using professional judgement and discretion’ (BASW 2011, 2025. P7)

This may be one to one, in a facilitated group or in a peer-led process.

There are many models of practice supervision that have merit, but most valued approaches advocate combinations of:

- reflection

- critical analysis,

- support,

- safe space (including psychological safety),

- safe challenge and honesty,

- emotional intelligence (between parties)

- clarity on standards and expectations

- keeping the outcomes and experiences of people using services at the forefront.

A recent addition to supervision guidance is the SWU-BNU Reflective Supervision: Best Practice Guide that is based on much of the research underpinning this toolkit.

https://swu-union.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/SWU-BNU-Reflective-Supervis…

Practice supervisors also help to mediate between managerial or organisational pressures and imperatives and the professional needs of social workers in practice. It is also important to identify continuing professional development and learning needs, and in supporting access to resources to meet those needs. Supervision should provide or be aligned with the process of annual personal development review, the early raising of areas for development and the provision of career and development resources.

Supervision as a joint responsibility

Organisations need to ensure social workers have appropriate and regular access to supervision from an appropriately skilled supervisor. But the success of supervision requires joint effort.

Both social workers receiving supervision and supervisors have a professional responsibility to ensure supervision is effective. This dual responsibility is reflected in regulatory standards e.g. the regulator Social Work England’s standard 4.2 ‘Use supervision and feedback to critically reflect on, and identify my learning needs, including how I use research and evidence to inform my practice’

BASW guidance on Code of Ethics and supervision 12: Using professional supervision and peer support to reflect on and improve practice Social workers should take responsibility for seeking access to professional supervision and discussion which will support them to reflect and make sound professional judgements based on good practice. BASW expects all employers to provide appropriate professional supervision for social workers and promote effective team-work and communication. |

A framework for reflective supervision

Reflective supervision can be extremely helpful for a person’s health and wellbeing (Hyrkäs, 2005). It can bring benefits to organisations and teams and its ultimate purpose is to improve outcomes for the people social workers work with.

A simple guide to establish good supervision can be for the social worker to consider the Who Where When?

| Who? | For reflective supervision, it is vital that you feel able to open-up and talk to someone who you trust. That might be the person assigned to you. But there may be another supervisor, manager or practitioner in your team or organisation who you believecould provide this more effectively. Identify this person, discusswith your line manager and try to build a supervision arrangement which will be most beneficial for you andthe people youwork with. Thiscould be in addition to a clear line management arrangement with someone else As a professional social worker working with a supervisor, your contribution to the process is as important as their’s. This is your time, it is also your opportunity to create knowledge and understanding for yourself and the supervisor through the positive effort you make and ideas you contribute in the session. |

| Remember | Remember, it is your opportunity to reflect, makesure the person helps you to do just that! |

| Where? | It is important that the location is not only a quiet place in order to have appropriate conversations, but also somewhere that is safe. Find somewhere that is quiet and that you feel comfortable. Find somewhere that works for you. Increasingly supervision is happening remotely by videoconferencing or telephone. It is important to take the time to set up the best connection and use the best technology available to prevent problems such as loss of connection or interference. Video contact can be excellent especially if sound and vision are clear. But telephone supervision can be preferable if less subject to interruption. Discuss and plan for your technology needs with your supervisor/supervisee. |

| Remember | Remember, it is your opportunity to reflect. Make sure your organisation and teamcreate the environment to helps youto do just that! |

| When? | Reflective supervision should be protected time, it is a good idea to create a plan a with your supervisor so that your reflective time is booked well in advance and this will also strengthen the value and importance of reflective supervision. Reflective supervision should therefore be organised to take place once a month. |

| Remember | Remember reflective supervision is protected time,work with your supervisor/supervisee and colleagues to make this happen. |

Becoming a practice supervisor

Practice supervision is a skill that social workers may need to develop at different points in their careers as they move into various supervisory roles. They may be early career social workers studying to be a Practice Educator (e.g. working for their Practice Educator Professional Standards (PEPs) stage one in England and equivalent stages of development in the other nations), learning from working with a social work student. Or they may be Practice Mentor Assessors, supporting social workers to complete e.g. post-qualifying statutory mental health training under the different legislations across the four nations.

Supervisors need training and good supervision themselves to develop into their role with skill and confidence . For instance, in England this has been recognised in the Practice Supervisor Development Programme for children and families social work. All social workers moving into supervisory roles should have access to sufficient, appropriate training.

This applies equally to social worker supervisors in the NHS, private and voluntary sector contexts.

Supervision is sometimes provided in action learning and/or peer group contexts. These can be powerful and beneficial and can supplement one to one supervision. In some work contexts – e.g. where work with service users is primarily done in groups – group and peer supervision may be the main form. Group and peer supervisions ideas are explored in Chapter about Teams.

Practice leadership

There has been a lot more interest in recent years in the leadership that all social workers can bring to practice and this is embedded in the Professional Capabilities for Social Workers in England in the domain of ‘Professional Leadership’.

Practice leadership may be provided by someone in a specific role – e.g. by a Principal Social Worker in England or a Consultant Social Worker in Wales, a specialist supervisor – but all social workers have professional responsibility to develop professional leadership skills. Put simply, this means having the knowledge, skills, and confidence to promote the best of social work, its practices, values, and ethos wherever you work.

Social workers with specific practice leadership roles have a crucial part to play in enhancing the wellbeing of colleagues. This may be through their provision of supervision, support, and advice – helping to create safe space for practice and clarity about standards and expectations. It should also be through enabling social workers to access the ongoing learning and development support they need.

A learning culture vs blame culture

People in formal practice leadership roles need to work closely with workforce managers, other managers, and organisational leaders to ensure there is investment in social work professional development and a commitment to developing a learning culture. This is characterised by a commitment to learn and reflect when things go wrong and when they go right, recognising that instincts towards ‘blame’ and ‘scapegoating’ – where individuals seem to carry responsibility for problems or failures with many contributory factors – should be rejected. Blame and scapegoating are not the same as accountability, but social workers reported in the survey that they still feel at risk of this.

Practice leadership – and a commitment to developing professional leadership and professionalism amongst all social workers - should help to promote a learning culture. If this isn’t how things work in an organisation, start small:

- With colleagues, create a reflective and learning approach in your part of the organisation through creating some space and time.

- Try to chart the benefits for staff wellbeing and practice over time

- Talk to people using services about what they expect and want from social workers, to inform learning topics and approaches

- Seek support for the approach from managers and organisational leaders

- Ask to provide a presentation or workshop to other parts of the organisation about the benefits

- Over time, work up formal proposals to managers and organisational leaders about how learning and opportunities to develop professional leadership and professionalism amongst social workers can benefit the whole organisation and people you work with.

The value of mentoring and coaching in social work

Mentoring and coaching are additional and different forms of support for social workers that complement professional, reflective supervision. They can provide different stimulation and opportunities for social workers to challenge and develop themselves. While mentoring has a long history in social work, coaching is a newer and, for many, less familiar form of support. It is gathering pace as more social workers experience its value. It is deeply grounded in strengths based approaches, finding one’s own solutions and being encouraged to gain new perspectives on practice, wellbeing and one’s own approach.

Both of these forms of support can be very valuable to support wellbeing, practice, confidence and professionalism.

Mentoring

Mentoring, distinct from coaching, involves the provision of support, guidance and encouragement by an experienced and expert social worker – in a more or less structured way - for less experienced and more ‘novice’ social workers or students.

Mentoring is a vital part of the development of most professions and can be crucible for integrating different forms of ‘evidence’ of what works into good practice: from research, professional experience, peer discussion, and from reflecting on learning directly from and with people using services.

Mentoring has a long history in social work in different countries through established cultures and embedded practices of valuing the support and advice of experienced social workers in the workplace.

The National Association of Social Workers (NASW) in the United States has a useful, well-developed concept of mentoring and its role in the transmission of knowledge, skills, values and ambition for the future as summarised here:

Mentoring in social work transcends mere duty; it embodies a noble calling to guide and inspire the next generation. Mentors serve as stewards of knowledge, sharing experiences and nurturing skills to empower students to become adept professionals dedicated to serving communities in need. Mentorship is pivotal in cultivating future leaders in social work, instilling values of compassion, empathy, and social justice. However, the mentorship gap remains a pressing issue, necessitating adequate support and recognition to enable mentors to fully engage in guiding their mentees.

The Transformative Power of Mentorship, NASW (no date) accessed 21 May 2025 https://naswnd.socialworkers.org/Advocacy/Public-Statements/ArtMID/54922/ArticleID/4030/The-Transformative-Power-of-Mentorship

However, this has not been consistently named and formalised in UK social work organisations. The importance of nurturing and valuing experienced colleagues, and developing their mentoring skills, may have played a part particularly in recent loss of experienced and skilled social work experts from the workforce early (BASW 2024) Responses to many recent surveysand investigations (see Chapter two) indicate a lack of consistent, overt valuing and incentives to stay for experienced social workers. Yet encouraging experience staff to mentor has great potential for mutual rewards for mentor and mentee.

Workforce development and the stabilisation of the workforce has tended towards a focus on inducting newly qualified social workers better rather than on maintaining the experienced workforce.

Research by Cook et al. (2022) highlights a specific gap in Continuous Professional Development (CPD) for experienced social workers in the UK and emphasises the importance of continuing to develop as a social worker throughout the mid and later stages of a career. .https://www.researchinpractice.org.uk/media/jo2plmhz/strengthening-the-workforce-retention-in-social-work-sb-web.pdf )

Her work also emphasises the importance of:

Generativity: Supporting other practitioners is a powerful motivator for experienced workers, who find ongoing meaning in sharing their learning and supporting the next generation of social workers. For example: supervision, mentoring colleagues, supporting ASYEs, practice education or taking on a workforce development role.

Cook, L (2022 p19)

The possibility of a valuable ‘win-win’ for experienced social workers, new social workers, people using services and employing organisations is often lost where workforce development approaches are not holistic in recognising the multiple benefits of maintaining experienced and expert staff cohorts.

BASW England offers a mentoring service for members – more information is available here https://basw.co.uk/about-basw/social-work-around-uk/basw-england/our-services/mentoring-service-basw-england

The Professional Capabilities Framework (PCF) for England

BASW hosts the PCF on behalf of the social work sector. This is a whole career framework for social work development in England https://basw.co.uk/training-cpd/professional-capabilities-framework-pcf which has also been influential in other parts of the UK and internationally. BASW and partners are developing the next iteration of the PCF, increasing its value for later career social workers. It is the only whole-profession, whole-career framework for developing and valuing experienced and later career social workers in England.

Action on mentoring: consider

|

Resources on mentoring in social work:

Department for Education, England guidance for managers and leaders in supporting social workers – Mentoring: https://www.support-for-social-workers.education.gov.uk/employer-standards/standard-6/mentorship?preferenceSet=True

Coaching

Coaching and mentoring are very different in their method, even though they can share similarities in their purpose. They both aim to engender confidence and the capability for more autonomy in others. But coaching does not presuppose the coach has subject expertise or the positional status of a mentor.

There are many general definitions of coaching. It is a wide field of practice, embracing diverse approaches to change. It is largely based around a ‘positive psychology’ perspective and a commitment to enabling people to develop and act on their own potential, solutions and powers.

Coaching, even if provided by a social worker coach, does not delve into the past, the causes of situations or underlying tangled dynamics at play. It focuses on what the person wants to achieve, what strengths and motivations they can draw on, and how they will use their energy and skills to get there.

A helpful description from Rogers (2016) proposes that coaching is:

“the art of developing another person’s learning, development, wellbeing and performance. Coaching raises self-awareness and identifies choices. Through coaching, people are able to find their own solutions, develop their own skills, and change their own attitudes and behaviours. The whole aim of coaching is to close the gap between people’s potential and their current state” (Rogers, 2016, p. 7).

Coaching has been increasingly recognised in social work both for its potential to support social workers directly in ways that complement traditional reflective supervision.

In profession-specific coaching, there is often some blurring with recognition of the value of a coach having subject knowledge even though they are not primarily providing guidance and advice (mentoring or supervision). In this vein, Grant and Kinman (2012) amongst others have noted the value of peer coaching as a benefit for social workers, highlighting that coaching techniques can embed social work knowledge within contextual exploration of change, realistic goals, reflective practice, and skills and resources available.

While still unfamiliar to many social workers, coaching may be described as a ‘natural fit’ because both professions ‘use comparable supportive processes that cultivate self-understanding and awareness to effect behavioural and attitudinal change’ (Triggs, 2020) and share many core values and ethical principles.

Coaching is gathering momentum in social work – for practitioners, managers and leaders. It offers a different way of helping people identify and decide what actions they can take on issues. It is also being increasingly recognised for its potential to inform direct practice. This includes enabling social workers to move beyond deliberate or inadvertent models of ‘fixing’ problems for ‘client’, towards approaches that empower self-driven change, focusing on strengths, agency and choice making. Coaching draws on the same well of ideas that already influence social work practice including Motivational Interviewing and Solution Focused Brief Therapy.

The BASW Social Work Professional Support Service (SWPSS)

Since 2020, BASW has been developing a coaching offer for social workers across the UK. Started during COVID with a charitable grant and now continuing with other funding and as a core service, BASW’s ‘Social Work Professional Support Service’ (SWPSS) is a free to access coaching service for social workers. It is now being funded by the governments in Scotland and Wales and resourced by BASW in England and Northern Ireland. This highly cost efficient and expert service is provided by trained and supervised volunteer coaches from across the UK.

Evidence from BASW’s coaching-based Social Work Professional Support Service (SWPSS) and from other burgeoning research is providing a growing evidence base of coaching’s value for worker wellbeing and for improving practices.

The SWPSS offers coaching focused on:

- Listening to explore experiences, issues and emotions that have come up during practice.

- Reflection to help explore behaviours and beliefs, career aspirations and personal goals.

- Resourcefulness to think about best practice guidance, career development and partnership working but also tools to support you to maintain your wellbeing, improve your motivation and/or self-confidence.

You can access the SWPSS Coaching Service online here https://www.basw-pss.co.uk/